By Jeff Greenwald.

Writer Jeff Greenwald joined ExperiencePlus! on a combined and modified version of our Bicycling Venice to Florence and Cycling Italy’s Culinary  Delights: Emilia Romagna Plus! Bologna itineraries that featured less bicycling, and a few extra culinary highlights. Though we may not visit all of the places Jeff describes we think he does an excellent job of emphasizing just how special and important this area of Italy is and has been gastronomically through the ages.

Delights: Emilia Romagna Plus! Bologna itineraries that featured less bicycling, and a few extra culinary highlights. Though we may not visit all of the places Jeff describes we think he does an excellent job of emphasizing just how special and important this area of Italy is and has been gastronomically through the ages.

Ten feet below Bologna’s vibrant Via Rizzoli, when the pedestrian underpasses are open, lie the remains of Via Emilia: an arrow-straight highway, 162 miles long, built by the Romans long before Jesus was in pannolini. Beginning at the coastal town of Rimini, Via Emilia connected a half dozen well-spaced cities – Forli, Faenza, Bologna, Modena, Reggio, Parma – before ending at Piacenza.

Today, the updated Via Emilia (SS9 on motoring maps) is Italy’s equivalent of Highway 49. Transecting the region called Emilia-Romagna, it’s a conduit linking the past and present. Before signing on for a bicycle tour of the province, I’d never even heard of Emilia-Romagna. But it so happens that everything I love about Italian cuisine, from pancetta to parmesan, originated along this ancient road.

“Food here is not a joke,” our guide declares as we sit down to our first dinner. It’s true. The menus of Emilia-Romagna are laced with myth and tradition. This is where tortellini was created, modeled after the navel of Venus; where the width of a tagliatelli pasta ribbon was decreed to be exactly one-one thousand two hundred seventieth the height of Bologna’s Asinelli Tower; where pork rumps are aged in dungeons. And this is the base from which a silk merchant named Pellegrino Artusi, presaging our own Alice Waters, created the concept of “Italian cooking.”

Our guide is correct. Food in Emilia-Romagna is a religion – and to visit is to worship.

Our guide is correct. Food in Emilia-Romagna is a religion – and to visit is to worship.

Parma may be an ancient city, but it’s so hip and cosmopolitan, you know you’ll never catch up. Our late afternoon stroll is filled with contrasting impressions: low sunlight illuminating the 13th century Baptistery, with its weathered walls of pink and white Verona marble; organic cotton jackets; and state-of-the-art espresso machines gleaming behind polished shop windows.

Parma was on the old Apennine pilgrimage route during the Middle Ages, and relics of that era remain – ceramic bowls mortared into the facade of the Bishop’s Palace, a sign that this was once a good place to get a bowl of soup. Today, it’s a good place for parmesan flan with balsamic vinegar, tortelli (i.e., ravioli) with greens, and tiramisu – our dinner is at a rustic trattoria decorated with vintage film posters.

After sundown, the cobbled streets of the old town swell with students and couples. Some huddle in tight groups, while others gather around tables covered with a dozen varieties of pizzas. Nighttime will bring the bar-to-bar pilgrimage that locals call la movida, “the nightlife” – a far more civilized phrase than “pub crawl.”

The next morning we climb onto our bikes and set off. A rural road carries us past farm fields dotted with brilliant red poppies, through small towns clustered beneath broken clouds and vivid blue skies. Scarecrows slouch in the fields, warning the birds away from the cherries. After an hour, we reach our lunch stop where we will feast on dried meats famous in the area.

Countless cured hams come from this region, but the most prized and expensive is culatello: a cut from the center of the pig’s rump. Unlike prosciutto – the dried haunch of the hind leg – culatello is hung in dingy cellars along the foggy banks of the Po River until it is coated in a revolting green mold. This mold sets up a chain reaction that, as with cheese, breaks down the protein chains. In this restaurant’s subterranean vault, an obstacle course of culatellos – about 5,000 in all – droop from the low ceiling. The choicest cuts are marked with small signs, already reserved for their buyers, a highly exclusive club that includes Prince Charles and Armani.

Countless cured hams come from this region, but the most prized and expensive is culatello: a cut from the center of the pig’s rump. Unlike prosciutto – the dried haunch of the hind leg – culatello is hung in dingy cellars along the foggy banks of the Po River until it is coated in a revolting green mold. This mold sets up a chain reaction that, as with cheese, breaks down the protein chains. In this restaurant’s subterranean vault, an obstacle course of culatellos – about 5,000 in all – droop from the low ceiling. The choicest cuts are marked with small signs, already reserved for their buyers, a highly exclusive club that includes Prince Charles and Armani.

Lunch is a cold-cut orgy. We dine on salumi (the plural of salami), a lovely pancetta, two kinds of prosciutto, warm spalla cotta (cooked pork shoulder) and lardo: pure white fat with a mild, melt-in-your-mouth flavor, like pig butter.

The famed culatello arrives, shaved thin as onion skin and equally translucent. Aged 18 months, it has a powerful, almost fishy taste that requires many goblets of the sparkling red Fortana Rosso to wash away. Pig-butt meat, apparently, is where my kosher-bred taste buds draw the line.

Just west of Modena lies and area famed for its balsamic vinegars. At small factories, the boiled must of the local grapes is aged at least 12 years and distilled in a series of wooden barrels of ever smaller sizes. It’s a careful, complicated process that Giovanni Cavalli, the passionate vinegar master, must explain five times – but once I understand it, the 80 Euro price tag on a 3-ounce bottle makes perfect sense.

Cavalli leads us among the barrels and offers us samples served in tiny spoons. The aceto balsamico is thick, and the color of molasses, but the taste transcends description. Sweet yet sharp, pungent and woody, it is the most complex and delicious flavor I’ve ever experienced: the world’s most sophisticated candy.

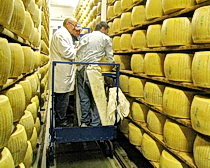

We awaken the next day to heavy clouds and race through the rain to a parmesan co-op. Here cheese master Giulliano  Lusoli oversees the production of 20 to 25 wheels a day, on behalf of the local dairy farmers.

Lusoli oversees the production of 20 to 25 wheels a day, on behalf of the local dairy farmers.

The factory floor is spotless, with a long row of cone-shaped copper vats in which milk is mixed with veal rennet. Heated and stirred, the liquid separates into siero (whey) and cheese, which Lusoli tests by hand until it reaches the perfect texture. It’s then pulled from the vats in cheesecloth slings, placed in molds and dropped in a tub of brine for a couple of months.

We sample three varieties of Parmigiano-Reggiano, aged 12, 22 and 34 months. Along with age, there’s pedigree: upland and lowland. The difference, Lusoli explains, is diet. While lowland cows eat alfalfa and wheat, the upland cattle (living at about 4,000 feet) dine on a mixture of grasses, wildflowers and herbs. Dribbled with local balsamic vinegar, the parmesans are a revelation, with aromas and finishes distinctive as any wine. After dozens of tiny portions, I have eaten about a pound of cheese.

“We’ll ride it off,” our guide assures me.

Maybe, but not in Italy.

When we do cycle, it’s fabulous. Riding from Faenza to Brisighella, we pass between rural vineyards and olive groves, grinding up curvy hills lined with wildflowers. Then down we zoom, pedaling furiously, the wind in our hair. Pulling up alongside Brisighella’s plaza, we’re lured immediately into the local gelateria, where the feisty proprietor claims she’s just made “the best banana gelato in the world.” No argument there from me.

Founded more than a millennium ago, Brisighella – with its sun-washed and wind-sheltered hills – produces the region’s best olive oil. Sure enough, we are called into a tasting room to sample several varieties, including Nobil Drupa, the town’s signature product, a costly EVO with the pungent aroma of newly mown grass. “This oil speaks for us,” expounds Giulliano Manduzzi, who may be the most passionate olive oil artisan in Italy. “It speaks about our people, about our farmers, about our ancient agricultural tradition. This oil is like our flag!” He swells with pride. “We’re very proud to show you this oil from our medieval village.”

Manduzzi’s enthusiasm is contagious. Sipping the oil, I feel like an honored ambassador. I’m tempted to set up a consulate – right next to the gelateria.

The ancient Via Emilia knits all these towns together and gives them a shared history. But on a culinary level, it was one man – born in Forlimpopoli – who gathered all Italy’s flavors and created the very notion of Italian cuisine. Pelligrino Artusi (1820-1911) was a marvelous writer and voluptuary who crisscrossed the nascent Italian Republic during the mid-1800s, collecting hundreds of regional recipes in his venerated “Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well.” But as wonderful as the dishes are, it’s Artusi’s droll commentary that makes the book:

“Life has two principal functions: nourishment and propagation of the species. Those who turn their minds to these two needs of existence, who study them and suggest practices whereby they might best be satisfied, make life less gloomy and benefit humanity.”

The recently opened Casa Artusi is a state-of-the-art culinary institute that serves as a research center, restaurant and cooking school. As one of our final activities, our group is invited to try our hands making piadina, a simple, round Italian flatbread. Our “laboratory” is an industrial kitchen, where each of us is assigned a chef-tutor. Under their sometimes exasperated eyes, we mix, pound, roll and fry our little parcels of dough.

This might seem a simple task, but – as is often the case with cooking – it’s the simple things that get you. My result, I fear, would not have pleased Artusi, who may well have buried my lame efforts with the remains of the Via Emilia. But I found it delicious, smothered in a thick preserve made from local figs.

My visit to Italy, like all visits to Italy, was too short. But when I return to Emilia-Romagna, I will try to spend more time in the saddle and more time at the Casa Artusi. Because cooking, I think, is a bit like cycling; no matter where you end up, it’s more satisfying to have arrived there yourself.

This article originally appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle. Photos courtesy of Jeff Greenwald and ExperiencePlus!